When a Police Investigatory Stop Crosses the Line

By H. Michael Steinberg Colorado Criminal Defense Lawyer

Introduction – Your Rights Under the Fourth Amendment

While I have written on this subject before, a recent Colorado case, People v. Oliver (2020) has reminded me of the critically important reasons why each of us should know and understand our rights to privacy.

The Fourth Amendment of the United States Constitution protects all of us from unreasonable searches and seizures by the government. The Fourth Amendment, however, is not a guarantee against all searches and seizures, but only those that are deemed unreasonable under the law.

Here is the text of the Fourth Amendment:

Amendment IV

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.

The “core,” “basic purpose,” and “central concern” of the Fourth Amendment is the protection of liberty and privacy against arbitrary government interference. Therefore, the “warrantless” seizure of persons and property is “presumptively invalid” and the burden of proving the lawfulness of the seizure falls to the government.

“[i]t is the right of every person to enjoy the use of public streets, buildings, parks, and other conveniences without unwarranted interference or harassment by agents of the law.”

People v. Aldridge, 674 P.2d 240 (1984)

When a Lawful Investigatory Stop Becomes Unlawful

The right of a police officer to conduct a stop of any person in Colorado is governed by the following law:

Section 16-3-103 – Stopping of Suspect

(1) A peace officer may stop any person who he reasonably suspects is committing, has committed, or is about to commit a crime and may require him to give his name and address, identification if available, and an explanation of his actions.

A peace officer shall not require any person who is stopped pursuant to this section to produce or divulge such person’s social security number. The stopping shall not constitute an arrest.

(2) When a peace officer has stopped a person for questioning pursuant to this section and reasonably suspects that his personal safety requires it, he may conduct a pat-down search of that person for weapons.

What Constitutes “Reasonable Suspicion” to Conduct a Lawful Investigatory Stop?

The term “reasonably suspects” as used in CRS 16-3-103, is not precisely defined under Colorado law. The term has been traditionally defined by what it “is not.”

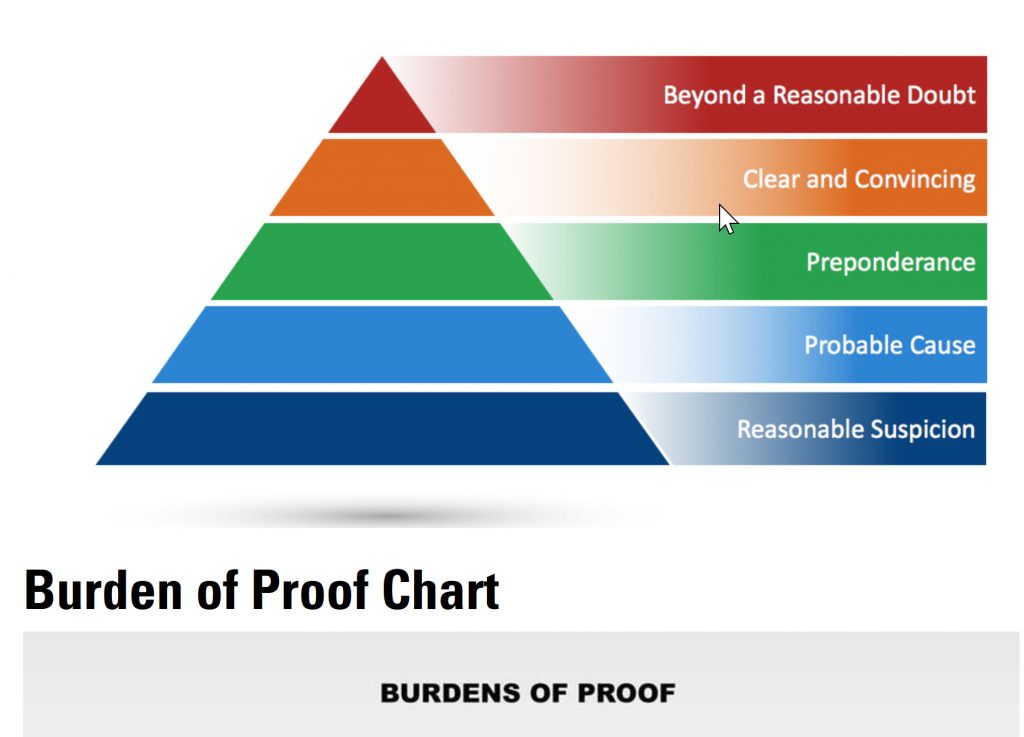

Reasonable suspicion means information known to the officer which amounts to more than a mere hunch or generalized suspicion, but less than probable cause to arrest.

A subjective and unarticulated hunch of criminal activity will not support the requirement that reasonable suspicion exists before an investigatory stop is made.

An officer who conducts an investigative detention must do so on the basis of more than an inchoate and unparticularized suspicion or hunch.

People v. Rahming, 795 P.2d 1338 (Colo. 1990)

[I prosecuted the Rahming case as an Arapahoe County Senior Deputy District Attorney in the late 1980’s. As a young Deputy District Attorney, I attempted to establish legal support for the stop of several suspects the police had identified as persons the police believed were about to commit a crime.

The Judge, at the time Judge John Leopold, disagreed, …. and he was right. The Rahming case is a watershed case often referred to in Colorado’s criminal courts. Here is a link to an article I drafted some time ago that takes a very close look at the issues in Rahming and other cases.]

Burdens of Proof as Identified by Levels of Evidence Required

Examples of conditions or circumstances which may lead to the development of reasonable suspicion include:

Persons fitting descriptions of suspects wanted for the commission of crimes;

Vehicles fitting descriptions of those used in the commission of crimes;

Persons fleeing and eluding upon sight of officers;

Persons or vehicles are seen leaving areas where crimes have been committed; or

Persons are behaving or maneuvering vehicles in a manner indicating criminal activity.

Brief Summary: Colorado Law and Branching Analysis of Police Citizen Encounters

Police-citizen interactions are classified as one of three types:

1. Consensual contacts,

2. Investigatory stops, or

3. Arrests.

While consensual encounters are not thoroughly addressed in this brief article, essentially a consensual encounter means an individual targeted by the police officer for an interview.

In a consensual encounter, a person is approached by a police officer who then initiates a conversation. No level of evidence is necessary to contact that person.

For example, if a police officer engages someone who is sitting on a park bench, the officer may ask questions of that individual. The individual has the right to refuse to answer, walk away, refuse to speak, and refuse to provide identification.

On the other hand, a field interview or investigatory stop is an escalated form of police intrusion. It is not conducted as part of a consensual encounter. The difference here is most often related to ‘motion.’

If a person’s physical progress – such as walking or driving – is impeded in some way by the police, the contact is treated as an investigative detention and requires that police officers have reasonable suspicion that the individual being contacted is engaged in illegal activity. Also, a consensual encounter cannot involve the use of commands, force, or lights and sirens.

If a reasonable person would not feel free to leave under the facts of the contact, then the encounter is not a consensual encounter, it is an investigatory stop.

A police officer who demonstrates their authority in a manner that restrains the individual’s freedom of movement in such as way that the person reasonably feels “compelled to comply,”… is clearly no longer engaged in a consensual encounter. The contact also has escalated into and has become an “investigatory stop.”

An investigatory stop is constitutionally valid if three criteria are met:

(1) the officer must have a reasonable suspicion that criminal activity has occurred, is taking place, or is about to take place;

(2) the purpose of the intrusion must be reasonable; and

(3) the scope and character of the intrusion must be reasonably related to its purpose.

The Next Stage: An Arrest – and – Probable Cause

Under Colorado law, an investigatory stop based on reasonable suspicion, can and often does escalate into an arrest, if certain other factors are present.

An arrest requires not just reasonable suspicion but the higher level of evidence referred to as probable cause … that the person contacted and then arrested …has committed, is committing, or is about to commit a crime.

An officer makes an arrest by physically restraining a person or by using authority in order to show that the individual is clearly not free to leave. The officer must have probable cause that the individual committed a crime in order to make the arrest.

Probable cause is a significantly higher standard of evidence than reasonable suspicion. Probable cause requires facts or evidence that would lead a reasonable person to believe that a suspect has committed a crime.

A police officer has probable cause and may make an arrest when:

He has a warrant commanding that such person be arrested; or

Any crime has been or is being committed by such person in his presence; or

He has probable cause to believe that an offense was committed and has probable cause to believe that the offense was committed by the person to be arrested. (16-3-102)

An investigatory stop is a temporary detention for the purpose of investigating activity that reasonably implies criminal conduct. However, if and when the police use levels of force associated with arrests such as physical restraint, detention inside police vehicles, a display of weapons, or the use of handcuffs,…. these especially intrusive factors can escalate a lawful investigatory detention into an arrest.

The Duration of the Investigatory Stop Can “Create” an Arrest

If, during an investigative detention, a police officer detains individual longer than is reasonable and during which time evidence amounting to probable cause is not established, that person must be released. What constitutes a “reasonable period of time” is evaluated by Colorado courts based upon the totality of the circumstances of the case in question.

Several courts have found that an “investigative detention ” that exceeds 20 to 30 minutes, without developing probable cause, is by definition, “unreasonable.” However, there is no hard and fast rule. Each case is judged on the facts of that case.

A Closer Look: Crossing the Line – When An Investigatory Stop Turns Into an Arrest

The police are permitted to pat down and even handcuff suspects during an investigative detention under certain conditions which call into question an officer’s personal safety, such as an articulable fear that a suspect is armed,

Such a use of force alone does not automatically convert an investigatory detention into an arrest. Law enforcement officers are allowed to use reasonable measures to ensure their safety during an investigatory stop, again, only if the use of such force is a reasonable precaution for the protection and safety of the officer.

It is axiomatic, however, that the use of force or restraint, such as handcuffs, “increases the degree of intrusion on an individual’s privacy and liberty and heightens the concern of the courts as to whether the action taken exceeds what is reasonably necessary.” People v Oliver.

Once officers have ensured that a suspect handcuffed for officer safety is unarmed and poses no risk to the officers, (as in the recent case of People v Oliver –, decided in 2020), the police must remove those handcuffs.

Leaving handcuffs on for the entirety of the stop, in the Oliver case, approximately two hours, escalated a lawful investigative stop into an unlawful arrest.

In the words of the Oliver Court:

“…. where initially reasonable concerns regarding officer safety have been dispelled and the individual being detained has been identified, the continued use of handcuffs transforms an otherwise proper investigatory detention into an arrest.

Here, officer safety concerns had been dispelled because ‘Oliver’s pat-down by officers revealed no weapons, he was outnumbered by police, his identification had been ascertained revealing no flight risk or safety concerns, and he was cooperating.’”

In Oliver, the officer heard multiple shots coming from an apartment complex and seconds later saw the defendant Oliver, and only Oliver, fleeing the area. When Oliver was instructed to stop, he ran faster. The Officer then heard screams coming from the complex.

These are precisely the kind of specific and articulable facts that will support an inference that a crime had been committed and that the suspect may have been involved and therefore the detention of that suspect was justified. attempted to evade him. Thus, drawing his weapon until cover arrived was a reasonable measure to ensure his safety.

The Rub: Leaving the Handcuffs On Too Long

The Olive Court found that placing handcuffs on the suspect before performing the pat-down search was reasonable due to the possibility that he might be armed. It was also found that it was reasonable to leave Oliver in handcuffs while obtaining his identification until the officer could ascertain whether he presented a danger due to having outstanding warrants.

The issue was this: because the officer left the handcuffs on for two hours this act was the functional equivalent of an arrest:

“[W]e hold that where initially reasonable concerns regarding officer safety have been dispelled and the individual being detained has been identified, the continued use of handcuffs transforms an otherwise proper investigatory detention into an arrest.”

The Motion to Suppress: the Tool use Prevent the Use of Illegally Obtained Evidence at Trial

Quick review – the investigatory stop in Oliver became an unlawful arrest when officers failed to remove Oliver’s handcuffs after officer safety concerns had been dispelled and in the absence of other threatening conditions. Therefore the investigative detention escalated into an arrest and since the evidence at the time of the arrest would not support a finding of probable cause, Mr. Oliver’s arrest was unconstitutional.

When an arrest is unconstitutional, any evidence derived from or obtained as the result of the illegal conduct of the law enforcement officers is improperly obtained fruits of the conduct in violation of the defendant’s rights.

Any evidence obtained as a result of an unlawful arrest must be suppressed – under the doctrine referred to and well known as the “fruits of the poisonous tree.”

In the Oliver case, because the evidence obtained after the arrest should have been suppressed at trial, the Trial Court’s failure to suppress that evidence resulted in the reversal of the defendant’s convictions.

“A person charged with a crime requires the guiding hand of counsel at every step in the proceedings against him. Without it, though he be not guilty, he faces the danger of conviction because he does not know how to establish his innocence.”

United States Supreme Court in Powell v. Alabama, 287 U.S. 45, 69 (1932)

If you found any information I have provided on this web page article helpful please share it with others over social media so they may also find it. Thank you.

Never stop fighting – never stop believing in yourself and your right to due process of law.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: H. Michael Steinberg – Email The Author at hmsteinberg@hotmail.com – A Denver Colorado Criminal Defense Lawyer – or call his office at 303-627-7777 during business hours – or call his cell if you cannot wait and need his immediate assistance – 720-220-2277. Attorney H. Michael Steinberg is passionate about criminal defense. His extensive knowledge of Colorado Criminal Law and his 38 plus years of experience in the courtrooms of Colorado may give him the edge you need to properly defend your case.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: H. Michael Steinberg – Email The Author at hmsteinberg@hotmail.com – A Denver Colorado Criminal Defense Lawyer – or call his office at 303-627-7777 during business hours – or call his cell if you cannot wait and need his immediate assistance – 720-220-2277. Attorney H. Michael Steinberg is passionate about criminal defense. His extensive knowledge of Colorado Criminal Law and his 38 plus years of experience in the courtrooms of Colorado may give him the edge you need to properly defend your case.

Colorado Criminal Lawyer Blog

Colorado Criminal Lawyer Blog